The plural of octopus is octopi.

But you would never know this from a dictionary. In its first (1909) and second (1989) editions, the Oxford English Dictionary gave only the two options octopodes and octopuses. Curiously, it did not supply a single example of the supposed form octopodes, but apparently reasoned from some etymological principle that this was the correct pluralization of the word.

In its third edition (2004), the OED added the option octopi and made the following comment:

The plural form octopodes reflects the Greek plural. The more frequent plural form octopi arises from apprehension of the final -us of the word as the grammatical ending of Latin second declension nouns.

This comment is misleading in two respects. In the first place, there is no ‘Greek plural’ to speak of. As the OED itself notes, there was never any noun octopus in classical Greek, let alone in a plural form octopodes. Second, ‘apprehension’ implies that it is unlearned and illegitimate – but regretfully common, and therefore perhaps acceptable – to treat octopus as a Latin noun of the second declension. As we will see, there is absolutely nothing wrong with doing so.

It gets worse. Henry Fowler, author of the famous Dictionary of Modern English Usage, wrote under the entry Octopus that ‘the Greek or Latin plural, rarely used, is -podes, not -pi’. Under the entry Latin Plurals he also made the sneering comment:

In Latin plurals there are some traps for non-Latinists; the termination of the singular is no sure guide to that of the plural. Most Latin words in -us have plural in -i, but not all, & so zeal not according to knowledge issues in such oddities as hiati, octopi, & ignorami.

Purism, however, also has its barbarisms, such as the quasiclassical plurals octopi and syllabi for octopus and syllabus, competing with octopuses and syllabuses. (The Greek plurals for these words are, respectively, octṓpoda and sullabóntes [🚨 sic!!🚨 ].)

Πουλύπου ὀργὴν ἴσχε πολυπλόκου, ὃς ποτὶ πέτρῃτῇ προσομιλήσῃ τοῖος ἰδεῖν ἐφάνη.

Make like the tangled octopus, who appears just like the rock he clings to.

Ubi manum inicit benigne, ibi onerat aliquam zamiam.

Ego istos novi polypos qui ubi quicquid tetigerunt tenent.

Whenever he lends a helping hand, he lays on some kind of damage. I know these octopi: whenever they touch something, they hold it fast.

– Aulularia 196–7

ΠΟΛΎΠΟΥΣ et accusandi causa πολύποδα καὶ πολύπουν dixerunt Græci à pedum multitudine. Unde illi quoque qui Græciam nunc incolunt ὀκτόποδα vocant.

The ancient Greeks called this animal POLYPUS (in the accusative case, polypoda and polypun) on account of its many feet. For the same reason, the modern inhabitants of Greece call it octopus. [2]

Rondolet appears to have been mostly right about the modern Greeks: according to the Lexikon zur byzantinischen Gräzität, the word ὀκτάπους [sic] is attested in medieval Greek as a name for the modern octopus. I haven’t, however, been able to track down the sources cited in the LBG’s entry, so I don’t have a sense of how ὀκτάπους was generally declined. Luckily this question is of only the faintest importance. In any event, by the seventeenth century, Greeks were calling this animal ὀκτωπόδια, as the naturalist George Wheler observed [3].

|

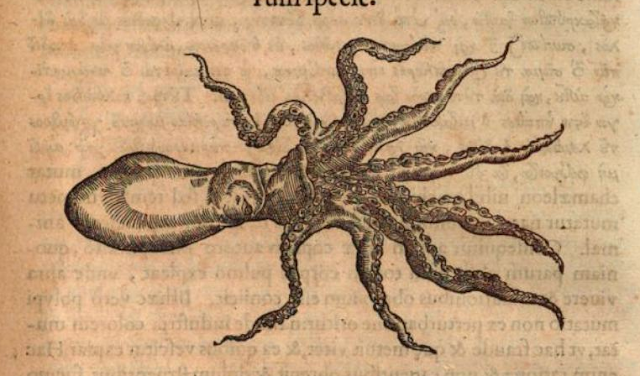

| Rondelet’s polypus. |

Two hundred years after Rondelet – in the early years of modern taxonomy – Carl Linnæus’ student Fredrik Hasselquist wrote a description of Octopodia, an eight-legged kind of cuttlefish which he had seen in the harbour of Smyrna. According to him, ὀκτωπόδια was what the local Greeks called this creature. [4]

Carl Linnæus later adapted Hasselquist’s entry for the 1756 edition of his Systema naturæ, and applied the name Sepia octopodia to the set of animals that we now know as octopi. He also remarked that Rondelet had called this species Polypus octopus: not quite accurately, for as you can see from the citation above, Rondelet had merely said that the Greeks called a certain kind of polypus an ὀκτόπους.

In 1788, when Johann Friedrich Gmelin revised Linnæus’ Systema naturæ for its thirteenth edition, he replaced Hasselquist’s coinage Sepia octopodia with Sepia octopus. Perhaps he thought that octopus was a more appropriate classical adjective than the puzzling octopodia. Or else he made a mistake. Or else his printer did. One way or another, this appears to have been the first modern taxonomic use of the word octopus.

In any case, Gmelin never meant octopus to be the standalone name of any animal. Octopus was rather an neo-Greek adjective which qualified a given animal as eight-footed, in this case a sepia. The neuter plural of it, meanwhile, was octopoda, which could be taken substantivally to denote the set of eightfooted molluscs. Similarly, Greek δίπους, ‘two-footed’, takes the neuter plural δίποδα, which means ‘bipedal animals’. Gmelin’s adjectival use of octopus is therefore a red herring, and does not correspond to modern English octopus. It has, however, come down to us as a taxonomic term. The order Octopoda, (or, if you prefer, the Octopods) comprises the eightfooted Cephalopods, which themselves make up a class within the phylum Mollusca.

It soon happened, however, that Gmelin’s adjective octopus became a noun in its own right, and soon the common name of the animal itself. This is the source of our English word octopus. The first example of this usage that I can find is in a lecture by Henry Baker at the Royal Society in November 1758. He defined three kinds of ‘Sea Polypi’:

First, the Polypus, particularly so called, the Octopus, Preke, or Pour-contrel: to which our subject belongs. Secondly, The Sepia, or Cuttle-fish. Thirdly, the Loligo, or Calamary. [5]

For Baker, unlike for Gmelin, octopus was not merely a description of the number of feet that an animal had, but the name of a specific beast. Here we are no longer dealing with a Hellenizing adjective, but a substantive patterned directly after polypus.

The decisive step was taken in 1798, when Lamarck wrote a taxonomic reorganization of some molluscs. [6] He distinguished four species of octopus: Octopus vulgaris, Octopus granulatus, Octopus cirrhosus, and Octopus moschatus. For Gmelin and Linnæus, octopus had been an adjective that specified a particular species of sepia or polypus. For Lamarck, however, octopus was the very name of the animal. It represented a genus which could be divided into species by the addition of disambiguating adjectives. Lamarck’s octopus was meant not to qualify, but to replace and supersede polypus.

So it did. Over the century following Larmark’s 1798 article, octopus displaced polypus as this animal’s common name in most European languages. Here are some examples from the OED:

The Octopus, which was the animal denominated Polypus by Aristotle, has eight arms of equal length. (1834)

The octopi also feed on conchyliferous mollusca. (1834)

The body of the octopus is small, it has legs sometimes a foot and a half in length, with about two hundred and forty suckers on each leg. (1835)

Help! The old magician clings like an octopus! (Robert Browning, 1880)

Young octopi, delicacy of the Japanese, hungrily searched about with their tentacles. (1942)

Now we have two words to distinguish from each other. There is octopus, the neo-Hellenistic adjective which Gmelin borrowed from Rondelet via Linnæus, and whose neuter plural substantival form, octopoda, begat English octopod(s). Then there is Lamarck’s octopus, a noun that denotes an animal in exactly the same manner as Latin polypus. I submit that as polypus only has one acceptable pluralization, polypi, only wanton pedantry could make us give its successor, the exactly analogous octopus, any other plural form than octopi.

We might even say that Octopods bears the same logical relationship to octopi as fishes does to fish, or louses to lice; in that the former refers to species of the same animal, and the latter to actual individuals. Examples of octopods are Octopus vulgaris and Enteroctopus dofleini. Examples of octopi are Pulpo Paul and Squidward Tentacles.

No comments:

Post a Comment